You are here

Science of Reading Myths and Misconceptions

Myths and Misconceptions about Learning to Read through Science-Based Reading Instruction

There are many myths and misconceptions surrounding learning to read and the use of curricula that align with the science of reading. Here are some of the most prevalent and most damaging in shifting to more effective and equitable practices.

Myth #1: Learning to read is a natural process.

Learning to read is a complex human process that is not naturally occurring. The human brain is hard-wired for spoken language – making learning to speak natural. Any child, unless neurologically or hearing-impaired – or are sensory-deprived - will learn to speak at some point.

Reading and writing, on the other hand, are man-made. The notion that simply surrounding students in a print-rich environment and fostering the love of reading will lead them to become readers may sound ideal, but that is not how learning to read works. We are not hard-wired to read; our brains repurpose different parts of the brain for reading to create a reading neural network. Immersing children in literature and language-rich environments is important, but not sufficient on its own to guarantee the development of the necessary literacy skills for successful reading. We are not hard-wired to read and because of this these skills must be explicitly and systematically taught to students along with providing ample opportunity for students to practice these skills.

(Dehaene, 2009; Lyon, 1998; Wolf, 2007)

The idea of “late bloomers” is another pervasive myth. This was known among researchers as the developmental lag theory, which said that difficulties in learning to read would fade as the brain matured and that early intervention was not needed—that the student just needed more time. Developmental lag theory has been disproven with evidence, indicating that for most students waiting does not work and is harmful. Evidence from three longitudinal studies has supported the skill deficit theory and discredited the developmental lag theory

Late bloomers are rare; skill deficits are almost always what prevent children from blooming as readers.

(Juel, 1988; Francis et al., 1996; Shaywitz et al., 1999; Torgesen, 1998)

Myth #3: Science of reading-aligned practice emphasizes phonics only.

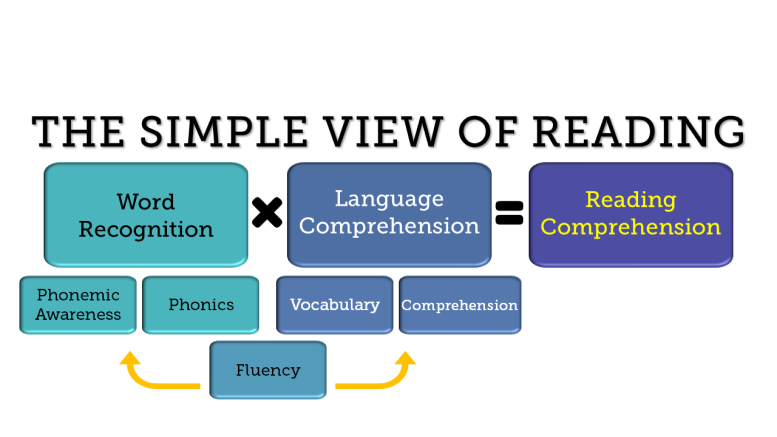

The science of reading is built on the Simple View of Reading and emphasizes the five components of reading, plus oral language.

(Gough & Tunmer, 1986)

This model developed by Gough and Tunmer organizes the skills needed to become a proficient and successful reader into two categories: word recognition and language comprehension. The Simple View of Reading is a basic formula for reading comprehension. It says this: reading comprehension is the product of word recognition skills and language comprehension skills. We need both variables in the equation for students to become skilled, proficient readers. Students need efficient word recognition or decoding skills where they are accurately and automatically reading the words on the page without the aid of context clues or pictures*. They also need fully developed language comprehension skills, which references the ability to understand language. In order for a student to understand text, they need to decode the words on the page and then make meaning of the words, sentences, and overall text.

*Use of context clues and pictures is an acceptable comprehension strategy. The use of context in comprehension refers to something quite different from the use of context in word recognition. Examples of using context to aid in comprehension are determining the meaning of unknown words, understanding words with multiple meanings, and understanding pronoun referents. The use of context to aid comprehension should be consistently encouraged by teachers, although some contexts are more helpful than others for this purpose.

The skills needed to become a proficient reader can also be seen in the Reading Rope model. (Scarborough, 2001) This model aligns with The Simple View of Reading but gives us a little more information on the skills that are required in each variable of the equation.

The top portion of the rope detail the skills needed in the language comprehension category shown here in red. These skills are background knowledge, vocabulary, language structures, verbal reasoning, and literacy knowledge. The word recognition or word reading skills are phonological awareness, decoding, and sight recognition.

As the language comprehension skills become strategic and word recognition skills become automatic, a student becomes a skilled reader. This means their reading is fluent and their language skills are adequate so that the reader isn’t having to focus their mental energy on either the language comprehension pieces or the word recognition pieces and they are able to focus on comprehending, taking in and understanding what they are reading.

♦♦Follow-up question: Why is phonics often focused on in conversations about the science of reading?

Students need to develop both word recognition and language comprehension skill sets to become successful and proficient readers. Minimal phonics instruction or teaching concepts incidentally as they come up in text is not enough instruction for most students. Phonics is often the focus of conversation around research-based practice because it is the weakest component of many programs which do not align with the science. All students learn best through explicit and systematic instruction which teaches students phonics concepts in a structured sequence where lessons are building upon one another. Additionally, there is not as much debate on how to teach vocabulary and comprehension, so this side of the equation is not as thoroughly discussed but is equally important in instruction and student reading. Quality instruction in all components of reading is essential for effective instruction. See the Selecting Scientifically and Evidence-Based Instructional Programs page for more information on criteria for effective instruction in all components of reading.

(Schwartz, 2019)

Myth #4: Science of reading-aligned practice does not promote independent reading of authentic literature.

The goal of evidence-based reading instruction is for students to be able to read any book of their choice successfully. Science of reading-aligned practice promotes the use of different texts for different uses. Students are encouraged to engage with the books that interest them for pleasure reading. During instructional time, specific texts are chosen for accurate practice and application of concepts taught in the lesson, as a model of text structure, and to build vocabulary and background knowledge.

Decodable text is the type of text that focuses on the phonetic code and presents words to students that follow the concepts that they have been taught. In this way, students are encouraged to attend to the code and use their phonics knowledge to decode words. When correctly employed the use of decodable text is a method that helps all and harms none. It provides a reliable pathway to moving students to accurately and successfully read authentic literature of their choosing. When students are able to apply their decoding skills with fluency, they are able to transition away from decodable books to less phonetically controlled, authentic text. Decodable text is purposeful and temporary as students build and practice their skills.

♦♦Follow-up question: How is authentic text used with beginning readers?

Authentic text is used with beginning readers in read-alouds to build vocabulary and background knowledge, model complex sentence and text structure, and build other language comprehension skills like inference or learning figurative language. When students master decoding skills, authentic text becomes decodable and can be used to build word recognition and language comprehension skills. Authentic text is always encouraged for enjoyment reading whether independently, via audiobook, or with the support of another reader.

For more information visit the Text Types: Decodable, Leveled, & Authentic webpage.

(Beck & Juel, 1997; Foorman, B.R. et al., 1997; Jenkins, J. R. et al., 2003)

Myth #5: Science of reading-aligned practice is a deficit model of reading instruction.

Science-based reading instruction uses data to identify skill strengths and deficits if a student is struggling, but this is an aspect of data-driven instruction and not a deficit model of instruction. In a deficit model of instruction, a population of learners are stereotyped as unable to learn. A deficit model poses reading struggles as a personal problem rather than a structural or instructional one. This is the opposite of what research tells us about learning to read. With the right instruction, instruction that is based on research and evidence, almost all students will become proficient readers. Since reading is not natural, students need to be taught the necessary skills.

Core literacy instruction based on the science of reading benefits all students and is a way to move the most kids to successful reading without intervention. Programs that are not based on reading research leave many children behind and contribute to the systematic deprivation of access to effective instruction.

(Lyon, 2002; Seidenberg, 2017; Stanovich & Stanovich, 2003)

Myth #6: Science of reading research and aligned instructional practice does not include English language learners or multi-lingual students.

The body of research commonly referred to as the science of reading is based on thousands of studies conducted around the world in many languages, including research on English language learners, multilingual students, and speakers of nonmainstream dialects. This research tells us that linguistically diverse students benefit from the same core reading instruction that benefits all students - instruction that includes phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and text comprehension (Cárdenas-Hagan, 2020). Incorporating home language knowledge and pairing skills with additional supports and a focus on oral language proficiency is beneficial and necessary for linguistically diverse students. Adequate assessments are necessary in determining student strengths and weaknesses to design instruction that will meet the needs of individual students.

See the Linguistically and Culturally Diverse Learners section on the Educator Resources webpage for more information on this topic.

(Cárdenas-Hagan, 2020; Goldenberg, 2020; The Reading League, 2022)

Myth #7: The three cueing system is helpful for English language learners.

To understand what they are reading, all students need to be able to read the words on the page and match those words up with words in their vocabulary. This includes students learning English as a second or multiple language. The goal of the three-cueing system is for students to determine unknown words by accessing information sources including meaning, structure, and visual. In this approach, students are encouraged to make informed guesses at a word, use context or other knowledge and experience to plug-in unfamiliar words. This is not an efficient method of reading for any student and encourages habits that can hinder reading development.

Imagine a reader comes to the word left blank above and uses guessing as their primary reading strategy. What might they guess? Will Ken feed a hen? Will Ken eat a hen? Will Ken see a hen? Using guessing as the reading strategy produces wildly different results in the meaning of the sentence. Additionally, students who are learning English while learning to read in English may not have as large of English vocabularies to guess the word correctly even when there is a great deal of context in the sentence.

(Cárdenas-Hagan, 2020; Goldenberg, 2008; Goldenberg, 2020)

Myth #8: Science of reading-aligned practice kills the love and joy of reading.

The goal of science-based reading instruction is for students to be able to pick up any book of their interest and enjoy it. In order to enjoy and love reading, one must have the skills to read. Practices aligned with the science of reading utilize read alouds to enjoy stories, build background knowledge, and develop comprehension skills. This transfers to independent reading as students build their decoding skills and ability to read independently.

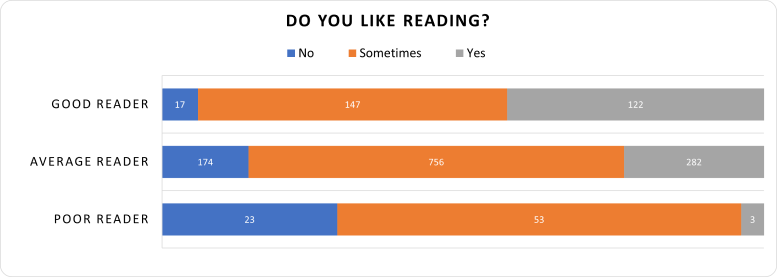

A body of research shows a unidirectional influence of literacy skills on enjoyment. Better readers are more motivated to read, including finding reading enjoyable and engaging and reading more often. Literacy skills impact enjoyment, but not the other way around. We have the tools to promote the joy of stories and the joy of reading for those students who are good readers, but there is no joy or love of reading without being able to read.

(van Bergen et al., 2021)

♦♦Follow-up question: What about students who don’t need phonics? Is a science of reading-based approach really just “drill and kill” leading to boredom and the dislike of reading?

All students benefit from systematic phonics instruction along with explicit instruction in all five reading components. The more students know about the language, the better prepared they are to read, spell, and write. Additionally, phonics instruction that is sequential provides opportunities for learning and practicing advanced reading skills. The decoding brain of skilled readers leads to deep reading.

Students need multiple exposures to new concepts, need practice with those concepts to build decoding skills, increase fluency, and allow for automatic reading and deep comprehension. Reading fluency is built like fluency of any other skill, and that is through direct instruction and practice. Effective practice is highly interactive and enjoyable as students are experiencing the thrill of learning and success. As mentioned above, the dislike of reading tends to relate to difficulty with reading and not too much practice.

(Wolf, 2008)

Myth #9: Science of reading is a program or pedagogy.

Effective pedagogy is based on the science of reading. The term ‘science of reading’ does not point to any one specific program or approach, but rather to practices that are aligned with research and backed by evidence. Pedagogical research tends to focus on instructional practices— not on specific curricula or literacy programs. A certain program may be better aligned to the science of reading based on the practices that it employs to teach the key areas of reading, but no program is "a science of reading program."

(Seidenberg, 2017; The Reading League, 2022)

Myth #10: Science of reading is a one size fits all approach.

Instruction that is aligned with the science of reading does not represent a one size fits all approach. All readers need to develop the same set of skills to become proficient readers and every student receives grade level instruction plus targeted instruction, but this is far from a one size fits all approach. Effective instruction includes differentiation based on students’ needs and abilities. Effective instruction must include the use of valid and reliable data to identify student strengths and weaknesses to drive instructional decisions.

“It is simply not true that there are hundreds of ways to learn to read […] when it comes to reading all have roughly the same brain that imposes the same constraints and the same learning sequence.” -Dr Stanislas Dehaene, Reading in the Brain

When teachers are armed with the knowledge and understanding of how skilled reading develops, they are better equipped to meet the needs of their students.

(Dehaene, 2009; Snow, et al., 1998; Just Read, Florida!, 2016; The Reading League, 2022)

Reference Page

Connect With Us