You are here

Stories of Promising Practice - All Means All - English Language Story

All Means All

All Means All

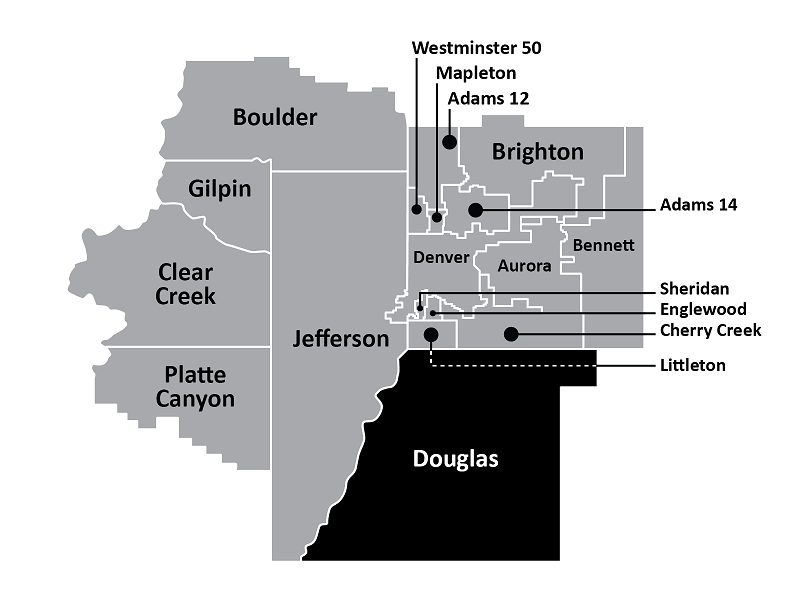

Douglas County School District

The lesson being taught on this spring day in this Douglas County School District middle school would be challenging for any adolescent -- a deep discussion among the classroom teens about the differences between showing empathy and showing sympathy.

The topic, undoubtedly, was even more confounding for Alexandra Guarda, a 12-year-old seventh-grader who a year ago traveled to the United States from Mexico and is now learning English and American education at Castle Rock Middle School.

Alexandra’s native language is Spanish, and she is classified as an “English Learner,” a linguistically diverse student whose English proficiency requires multi-levels of support to ensure she learns the grade-level content in English.

In the 2018-19 school year, more than 125,000 ELs were enrolled in Colorado’s public schools, roughly 14 percent of the state’s K-12 population. Federal and state laws outline districts’ obligations in how they can provide programs for ELs, including English language development and setting academic goals for students.

Douglas County School District provides a blended approach with an emphasis of pushing English language development services into the regular classroom rather than pulling students out of their classes for individualized instruction. This balanced ELD Programming seems to be working because academic growth of EL students is soaring, earning the district the annual ELPA Excellence Award.

The award identifies and awards districts that are in the top 25% growth percentile on the English Language Proficiency Assessment, the top 25% growth percentile on the Colorado Measures of Academic Success assessments in English language arts and math for English learners and the top 25% in those tests for EL students who have exited from the English Language Development (ELD) program.

In Alexandra’s homeroom class, English proficient students are mixed with ELs who are still learning English. Two teachers, both with English language development experience, co-teach the class, which is the norm in the Douglas County School District.

The social-emotional lesson was being taught in English but was augmented by an animated film. Additionally, teacher Sam Teres drew stick figures on the white board that visibly displayed the difference between empathy and sympathy.

Alexandra carefully read through a sheet in English that Teres handed out, which asked the students to consider broad questions such as whether they thought they were a more sympathetic or empathetic person. Classmates at her table, who also were English learners, talked with each other about the assignment.

Teres, while working with other students in the room, observed the ELs in the class, checking for body cues to see if they understood.

“I give the lesson in English, but I watch to see if they are getting it,” he said.

Alexandra began writing down answers.

“See,” Teres said from across the room after he saw Alexandra begin to write. “It looks like she is engaged. Sometimes, if I have to go and talk to her in Spanish, I will. But the goal is for her to understand it in English.”

In Castle Rock Middle School, only about 8 percent of students are ELs, which is among the highest concentrations in Douglas County School District, where only about 3,800 of the district’s 67,500 students are eligible for EL programming or about 5 percent.

Nevertheless, Douglas County six years ago changed how it instructed its EL student population, going to the blended model.

“Generally our schools co-teach and collaborate at the universal levels so that we have students who are in high-level rigorous coursework and then we tier instruction for those who need additional support for language based on their experiences, their needs and their strengths,” said Remy Rummel, English language development coordinator with the district. “We have really moved away from complete pullout. Research shows the pull-out method is the least effective programming for language development, and the collaborative structure is the most successful.”

In the secondary level in 2018, Douglas County EL students showed greater growth than non-English learners in the district and in the state on both math and English language arts assessments. They also had higher growth levels than the non-English learners in state in the PSAT and SAT tests.

“We can see our balanced programming is working because No. 1 our data shows it,” Rummel said. “We have students who are growing at an astronomical rate. They are gaining language proficiency as well as academic achievement and academic growth. We can also see a higher level of family engagement and empowerment in our buildings.”

Equity for all students has become a mantra within the district, Rummel said.

“We must provide equitable access to experiences for students no matter their linguistic background, no matter their needs as perceived by educators,” she said. “And equity work really leverages the strengths of students and provides access to courses and experiences for all students.”

Sam Teres, who teaches English language development at Castle Rock Middle School, said the goal is to give ELs the opportunity to be successful in the mainstream environment while still offering support.

“That being said, equality of opportunity is not the same as equality of access,” he said. “So we’re not just dumping kids in a mainstream class if that is not appropriate. We have to look at the individual needs of each student and make sure that the programming and placement of each student is appropriate.”

Teres co-teaches in general education classes as well as teaches English as a Second Language classes that are smaller and more sheltered.

“It wouldn’t be equality of access to take one of those students and put them in a regular language arts class where they would be sitting silent and not having comprehensible input,” he said. “So again we have to look at the individual needs of each student and place them appropriately.”

But the goal is for more inclusion.

“We get the best outcomes when students are part of the larger community and they are not, to use a bad word, segregated in their own little pocket of the school,” he said. “That does not produce valid outcomes for anybody. The rest of the school isn’t being exposed to the diversity of cultures and languages. And they are not really part of the community. When you foster that organic connection, with the whole school, then the kids are part of the whole community.”

At nearby Castle View High School, all of the school’s 115 EL students are in general education classrooms, said Jeanne Johnson, ESL teacher.

“While we are giving them supports, we are making sure they are getting the credits so they can graduate on time,” she said. “It allows them to learn English and learn content and also go through the high school system like everyone else instead of being isolated or just in an ESL program.”

ESL teacher who are supporting students in the general education population are able to learn the content and help differentiate so the students can understand, she said.

“It allows them to still be in that classroom, accessing that material and being able to do it pretty much independently. The beginning of the year it is a lot of us holding hands to understand the process of the teachers and the classroom structure and the student’s learning style. But eventually they do it on their own. And in other districts I don’t think that is necessarily happening because the students are put in sheltered classes.”

Connect With Us